On Thursday, as legal experts debated how courts would see the Louisiana law, various religious leaders in the state voiced excitement and worry about what the Ten Commandments measure portends.

Lawyers from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, and the ACLU said they planned to file a lawsuit next week against the new law.

“It’s true this Supreme Court hasn’t been the best on church-state issues but we think this will be a bridge too far. Nothing they have said remotely suggests they would allow Ten Commandments in every classroom, where students are a captive audience and required to attend,” said Heather Weaver, staff attorney with the ACLU’s Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief.

Some outside experts on church-state law sounded less sure.

“Now we are in somewhat uncharted territory,” said Michael Helfand, a professor focused on religion and ethics at Pepperdine University’s law school.

Efforts to infuse religion into government entities, including public schools, have increased in the past decade as the high court has sided with those who want fewer restrictions on religion. State lawmakers, particularly in conservative areas, have put forward hundreds of bills aimed at adding everything from public school chaplains and “In God We Trust” signs in school entranceways to public funding for religious schools through vouchers.

The Louisiana law is part of a new crop of measures stemming from a 2022 Supreme Court ruling in favor of a high school football coach whose contract was not renewed because of his postgame prayers at the 50-yard line. The ruling in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District threw out the test used for more than 50 years to decide whether a law violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

The Lemon test, named after a 1971 Supreme Court ruling, asked questions like: Does the law cause “excessive government entanglement with religion?” or “Does the law advance or inhibit religion?” In the football coach case, the Supreme Court said that the Lemon test is no longer good law and that instead judges should look at “history and tradition.”

Noting that the Bremerton ruling deemed the coach’s actions constitutional, the ACLU’s Weaver said reasoning differs from the Louisiana law because the court said his prayers weren’t “public” or delivered to a “captive” audience.

“Regardless of the Lemon test, there has always in this country been an understanding the government can’t favor one denomination or one religion over others. Here, not only is the state mandating the Ten Commandments, but the statute even says which version, and lays out the text,” Weaver said.

The law calls for a particular Protestant text based on the King James Bible, which differs from versions used by Catholics, Jews and others, much less those used by other religions with their own faith texts.

Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president of Freedom From Religion, said the new law is “overreaching.”

“The religious right, Christian Nationalist types and their legal outfits have been crowing since the Bremerton decision that somehow all the precedent against religion in public schools has been overturned. This is not the case,” she said. “The Supreme Court has been captured under Trump but my hope is it’s not ready to go that far.”

“There is no history of the Ten Commandments in our founding, in the Constitution, even though a lot of ignorant people might think it’s there,” she said, calling the law the “antithesis of the Bill of Rights.”

Pepperdine’s Helfand said it is true that the Founding Fathers invoked the Bible and the Ten Commandments when America was born, but they still called for people to be able to worship or not as they pleased. The legal debate now may shift to the question of coercion, he said. When is someone being forced to engage with a religion they do not embrace? Might that include seeing the Ten Commandments on their classroom wall?

“You still can’t prefer one religion over another,” Helfand said.

John Inazu, a religion and law expert at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that the Supreme Court that threw out a similar law in 1980 was operating under a different legal approach. The earlier case, he wrote in an email, “was decided under a very different approach to the Establishment Clause. The Supreme Court has since moved toward a focus on history, text, and tradition. But it’s not clear to me that the Louisiana statute survives even under the newer framework.”

Putting this version of the Ten Commandments into classrooms is not a long-standing monument or tradition, and it’s “blatantly religious and monotheistic,” Inazu wrote.

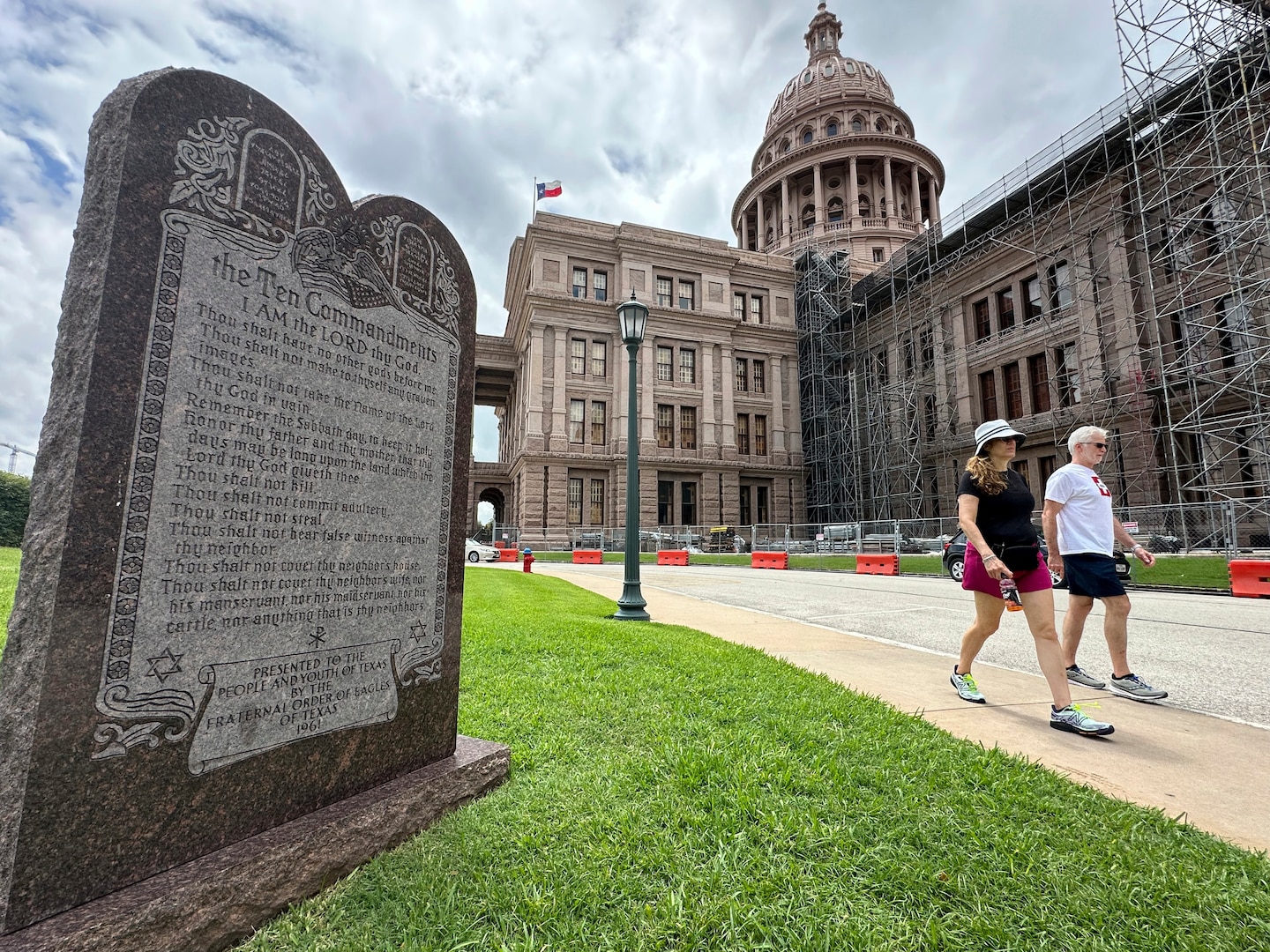

He noted the Supreme Court in 2005 upheld a Ten Commandments monument that sits on the Texas Capitol grounds in Austin. However, he said, the monument is separate from the Capitol itself, accompanied by a U.S. flag and Star of David as well as the seal of the civic group that donated it. The court said the monument had a secular purpose and did not imply a government endorsement of religion.

Among the flurry of post-Bremerton bills aimed at promoting religion in public schools was an effort last year in Texas to approve a Ten Commandment measure like Louisiana’s. It passed the state Senate but wasn’t taken up by the House. But its supporters gave voice to Americans who see the Supreme Court as righting the American ship after a half-century of wrongly separating church and state.

“There is absolutely no separation of God and government, and that’s what these bills are about. That has been confused; it’s not real,” Texas state Sen. Mayes Middleton (R), who co-sponsored the Texas bill, said last year.

One of the authors of the Louisiana law said the measure isn’t just about religion — nor, he said, are the Ten Commandments.

“It’s our foundational law. Our sense of right and wrong is based off of the Ten Commandments,” state Rep. Michael Bayham (R) told The Washington Post. He said he believes Moses was a historical figure and not just a religious one.

Those who object to the new bills say they reflect a country that is tipping into a new, dangerous phase in its balance of church and state, with people in power in some places seeking to assert a version of Christian dominance.

“Look, I love Jesus & the scriptures but this ain’t it. Raise a glass to LA looking like a fool on the National stage,” the Rev. Michael Alello, a Catholic priest in Baton Rouge, posted on X on Wednesday. “How much tax payer money will be wasted defending this in the courts, only for it to be overturned?”

But the Rev. Tony Spell, a Pentecostal pastor also from Baton Rouge, said the new law is an extension of his 2022 victory battling pandemic restrictions in Louisiana’s highest court. The justices had scrapped charges against him for leading religious gatherings despite lockdown orders.

“We have a conservative court in Washington,” Spell said, “but really, this is about the people, the warriors, the fighters.”

Movements to incorporate Christianity into every part of life have only grown since his court showdown, he said. Now he is working with groups raising money for the posters of the Ten Commandments they hope will soon be featured in classrooms across the state.

Asked about what the new law would say to people who aren’t Christian or don’t subscribe to that version of the Ten Commandments, Spell said: “Being offended is a choice.”

Mark Chancey, a Southern Methodist University professor who studies the use of the Bible in public schools, said the Supreme Court has put the country in a new era.

“It’s the wild west out there when it comes to government-sponsored religion,” he said, adding: “It’s not clear how these things will play out.”

#Louisiana #Ten #Commandments #law #tests #religionfriendly #courts #experts,

#Louisiana #Ten #Commandments #law #tests #religionfriendly #courts #experts