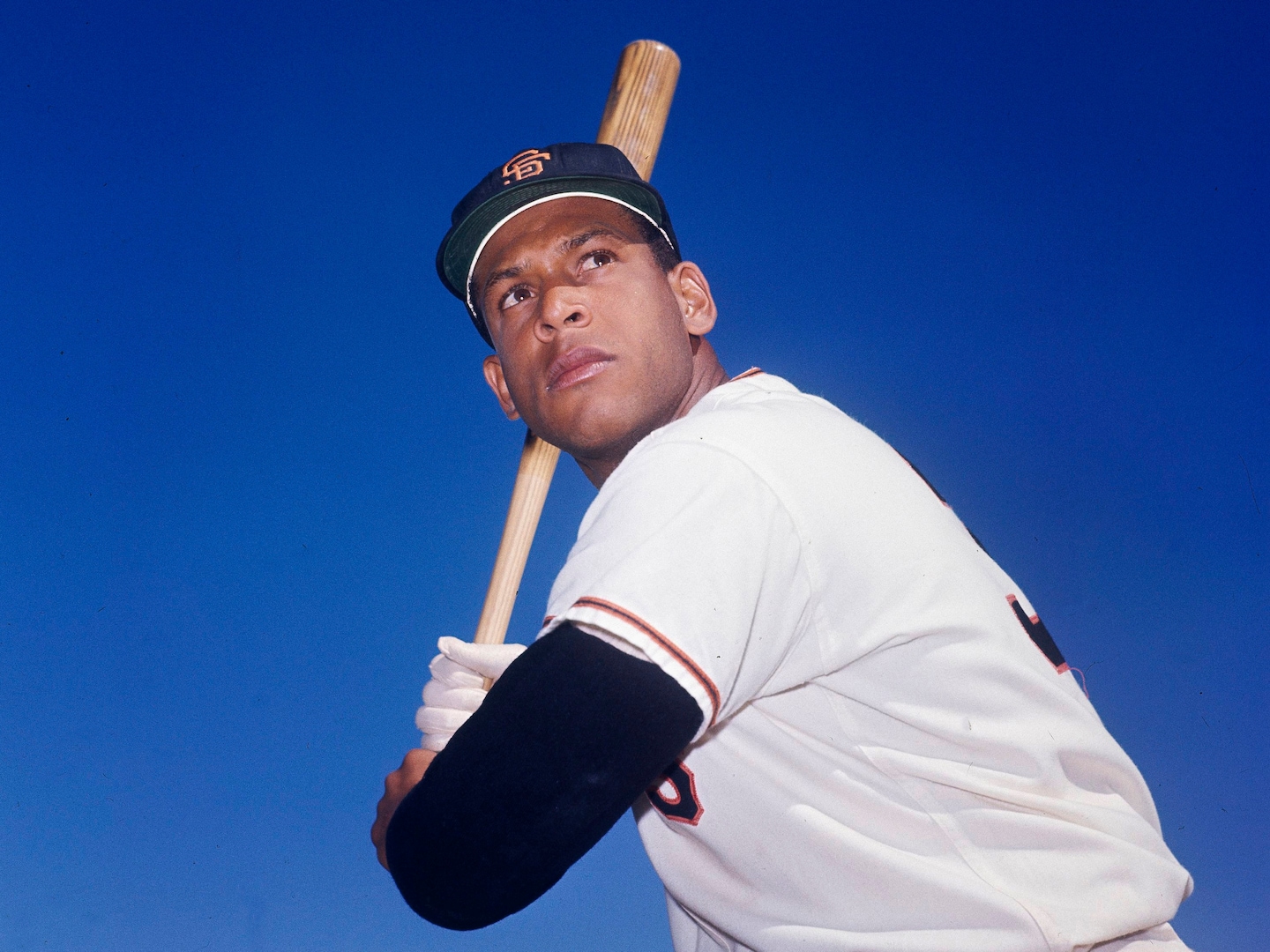

With his powerful hitting and exuberant style of play, Mr. Cepeda became an immediate star as a 20-year-old rookie with the Giants in 1958, the franchise’s first year on the West Coast.

He hit a home run in his first game and went on to win Rookie of the Year honors in the National League. He became a favorite with San Francisco fans, ahead of even star outfielder Willie Mays.

Mr. Cepeda was nicknamed the Baby Bull, in a nod to his father, Pedro, a Puerto Rican baseball star known as “El Toro.” His teammates dubbed him “Cha Cha” for his love of lively Latin music and his outgoing manner.

“You have to remember that Orlando was the most popular player when the franchise moved from New York,” team owner and managing partner Peter Magowan told the New York Times in 1993. “Orlando played the game with flamboyance. He was an all-around player. He got our fans interested in the team.”

In the early 1960s, the Giants had one of the most formidable lineups in the NL, with Mays, Mr. Cepeda and a third Hall of Fame slugger, Willie McCovey. During each of his first seven seasons, the right-handed-hitting Mr. Cepeda slugged no fewer than 24 home runs and drove in at least 96 runs. He finished his swing with a flourish of his bat above his head.

He had one of his most productive seasons in 1961, when he led the NL with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs, ahead of Mays and other stars, including Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson and Ernie Banks.

In 1962, Mr. Cepeda was at the heart of Giants team that finished the regular season with 101 wins and 61 losses — the same record as their archrivals, the Los Angeles Dodgers. In the decisive contest of a three-game playoff, Mr. Cepeda hit a sacrifice fly to tie the score, 4-4, in the ninth inning. The Giants went on to win, 6-4, and clinch the NL pennant, only to lose the World Series to the New York Yankees.

Mr. Cepeda was on deck when McCovey lined out in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7, as the Yankees hung on to win the series in the decisive contest.

During their years in San Francisco, Mr. Cepeda and McCovey alternated between left field and first base, leading to resentment from Mr. Cepeda, who believed he should have been the full-time first baseman. He also played in pain after injuring his right knee in a collision at home plate against the Dodgers in 1961.

His manager, Alvin Dark, never grasped the severity of his injury, Mr. Cepeda said, and hinted that Mr. Cepeda was not playing hard enough. Dark also ordered the Giants’ Latin American players to stop speaking Spanish and listening to music in the clubhouse. Mays, the team’s superstar, had to intercede to prevent a revolt against the manager.

“He treated me like a child,” Mr. Cepeda said of Dark in a 1967 interview with Sports Illustrated. “I am a human being, whether I am blue or black or white or green. We Latins are different, but we are still human beings. Dark did not respect our differences.”

Mr. Cepeda appeared in only 33 games in 1965 before having surgery on his damaged knee. He was traded in 1966 to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he was installed at first base and became the NL’s comeback player of the year. He emerged as a vocal leader on a team that included future Hall of Famers Bob Gibson, Lou Brock and Steve Carlton.

In 1967, Mr. Cepeda won the Most Valuable Player Award with a career-high .325 batting average, 25 home runs and a league-leading 111 RBIs. He helped propel the Cardinals — “El Birdos,” as he called them — to the World Series, in which they defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games.

“It’s not just his statistics,” teammate Mike Shannon said at the time. “It’s also what happens in the clubhouse. It’s intangible. I can’t really explain. Orlando is a prestige player, and we have him — the other clubs don’t.”

Although Mr. Cepeda’s hitting slumped in 1968, the Cardinals returned to the World Series but lost to the Detroit Tigers in seven games. He was then traded to the Atlanta Braves, for whom he had a stellar season in 1970, with 34 home runs. He later played for the Oakland Athletics, Boston Red Sox and Kansas City Royals.

He retired in 1974 with 379 home runs and a lifetime average of .297, including nine seasons at .300 or better. His accomplishments would typically have led to enshrinement in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but in 1975 Mr. Cepeda was arrested at San Juan International Airport while attempting to retrieve two boxes allegedly containing 170 pounds of marijuana.

He was convicted of possession of marijuana with intent to sell and sentenced to federal prison. He was released in 1979 after serving 10 months.

His reputation was shattered in Puerto Rico, where he had been hailed as the island’s greatest baseball hero after the death of Pittsburgh Pirates star Roberto Clemente in a plane crash on Dec. 31, 1972.

“I made a huge mistake,” Mr. Cepeda told the San Jose Mercury News in 1999. “When Roberto Clemente died, they said in Puerto Rico that at least we have Orlando Cepeda alive. So when I let everybody down, they got very mad. We are very emotional as a people. We are hard on people who mess it up.”

Orlando Manuel Cepeda Pennes was born Sept. 17, 1937, in Ponce, Puerto Rico, and grew up in San Juan. His father, Pedro “Perucho” Cepeda, was dubbed the “Babe Ruth of Puerto Rico” and played on Caribbean all-star teams with such stars of baseball’s Negro leagues as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell.

The younger Mr. Cepeda excelled in baseball and basketball during his youth and signed with the Giants, then still in New York, in 1955. His father died just before he was to play his first professional game for a minor league team in Salem, Va. Mr. Cepeda spent his $500 bonus on his father’s funeral and had to be persuaded to return to Virginia to continue his baseball career.

“I was only 17, and it was tough,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1991. “I lived in the black part of town, and on Sunday mornings I’d hear the people singing gospel music in the church across the street. I’d sit by the window in my room listening, and I’d cry from misery and loneliness.”

Nevertheless, he quickly advanced through the minors and reached the major leagues in only three years.

After his drug conviction in the 1970s, Mr. Cepeda struggled for years to rebuild his life. He became a Buddhist and 1989 attended a game in San Francisco. He proved so popular with fans that the Giants hired him as a goodwill ambassador, a position he held until his death.

His marriages to Ana Hilda Pino and Nydia Fernandez ended in divorce. His third wife, the former Mirian Ortiz, died in 2017 after 26 years of marriage. Survivors include five children from his marriages and other relationships.

For years, Mr. Cepeda was denied election to the Hall of Fame, which he attributed to his drug conviction. (He was also fined $100 in 2008 for possession of a small amount of marijuana.)

In his 15th and final year on the Hall of Fame ballot in 1994, Mr. Cepeda needed 342 votes to reach the 75 percent threshold for election. He fell seven votes short.

He finally won admission from the Hall of Fame’s veterans committee in 1999. He was the second Puerto Rican to be elected, after Clemente. The Giants retired his No. 30 jersey and in 2008 dedicated a statue of Mr. Cepeda at the entrance to the team’s stadium.

He also found redemption in San Juan, where a parade was held in his honor.

“The biggest victories come over yourself, when you control your mind and your destiny,” Mr. Cepeda told Sports Illustrated in 1999. “My life has been a drama of inner change.”

#Orlando #Cepeda #Hall #Famer #baseballs #Baby #Bull #dies,

#Orlando #Cepeda #Hall #Famer #baseballs #Baby #Bull #dies